| Welcome! to the ima EMAILER ~ October 2008 Issue |

The IMA EMAILER brings you news from ima pros Michael Murphy, Fred Roumbanis, Bill Smith and ima pro staffers across the USA and worldwide.

| ima Pro Michael Murphy Connects the Dots for Fall Fishing |

As children, we probably all have played with connect-the-dots books. Each page starts as a puzzle, and by connecting the dots, a pattern appears. Fall fishing can be the same way, puzzling at first, but by connecting the different parts, successful patterns emerge.

| The Drawdown Connection |

The first factor I’d like to discuss for the fall time of year is drawdown on drawdown lakes. Most common occurrences from my knowledge of drawdown lakes are from Missouri east to North Carolina, south to South Carolina, back across to Texas and about everything in between. In other words, the Midwest and Southeast, (with the exception of Florida). However, I presume a lake could be drawn down most anywhere there’s a way to do that and a reason.

The first factor I’d like to discuss for the fall time of year is drawdown on drawdown lakes. Most common occurrences from my knowledge of drawdown lakes are from Missouri east to North Carolina, south to South Carolina, back across to Texas and about everything in between. In other words, the Midwest and Southeast, (with the exception of Florida). However, I presume a lake could be drawn down most anywhere there’s a way to do that and a reason.

What causes the drawdowns, if you are not familiar with it, these lakes tend to be the result of damming so they’re actually reservoirs or man-made waters, not original natural lakes. The annual late season drawdowns on them are man-made too – and usually scheduled to take place after the summer recreational water use season is over – but while it is still decent weather for people who live around the lake to perform dock/ramp/retaining wall repair and so on. Also to lower the water level to prepare for spring rains to keep areas from flooding. In natural lakes, drawdowns are less common unless there is a dam of some sort that was put on a natural lake after the fact so that the water level can be controlled in much in the same way.

Why I’ve mentioned this is that drawdown lakes especially as you get toward Kentucky and farther south, you have a big crayfish move that coincides with when the drawdowns start.

| The Crayfish Connection |

In drawdown lakes or most any typical lake, crayfish generally live in water that’s 10-12 feet deep or less. On most lakes, they’re going to be in that opportune depth range. In clearer lakes, they may exist deeper as well, down to 20-30 feet.

In drawdown lakes or most any typical lake, crayfish generally live in water that’s 10-12 feet deep or less. On most lakes, they’re going to be in that opportune depth range. In clearer lakes, they may exist deeper as well, down to 20-30 feet.

In anticipation of winter coming, crayfish start to move into areas where they can burrow, and usually that starts around the drawdown.

When I say crayfish move, it’s not up or down. It’s sideways. They’re moving from a harder bottom to a softer bottom. Typically, they’re not changing depths, although survival instinct may tell them to go a little bit deeper if the water level falls too quickly.

The kind of move they make can be from sand to clay, sand to silt, from rock to clay – from a hard bottom, including sand in the category of a hard bottom to a softer bottom where they can build a winter home that will last till spring without collapsing in on them.

In the south, it can be water temperatures around 70 degrees when crayfish start to move. The farther south you go, the more it’s going to be like around 70, maybe even 75 when the crayfish start to migrate from summer feeding to winter burrowing locations. Once you get so far south, it just doesn’t happen. The farther south you go, the less likely the crayfish are to burrow and go dormant, just like the largemouth. The more likely they are to stay out year round. For example in Florida, Lake Okeechobee, there are crayfish that probably don’t burrow at all just because it stays warm most of the year. As you get way south, that whole low metabolism/hibernation phase of winter gets skipped.

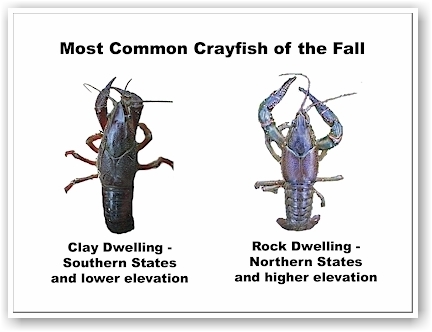

In the north, water temperatures around 65 to 60 trigger the crayfish movement. At the extreme north range, those crayfish being totally different species, probably don’t burrow at all because they’re more of a year-round rock-dwelling species. A lot of it is they’re just selective to the different environments. There’s just not a lot of clay for them to burrow on rocky lakes up north. The farther north you go, the less softer bottoms there are, and the more rock there is in general. So there are more rock-dwelling species of crayfish that stay out year-round. They don’t have a lot of clay to burrow in like the other clay-dwelling species.

In the north, water temperatures around 65 to 60 trigger the crayfish movement. At the extreme north range, those crayfish being totally different species, probably don’t burrow at all because they’re more of a year-round rock-dwelling species. A lot of it is they’re just selective to the different environments. There’s just not a lot of clay for them to burrow on rocky lakes up north. The farther north you go, the less softer bottoms there are, and the more rock there is in general. So there are more rock-dwelling species of crayfish that stay out year-round. They don’t have a lot of clay to burrow in like the other clay-dwelling species.

Where we see the most variety of clay-dwelling crayfish is in the middle belt where you have an overlapping ranges of different clay-burrowing species – Missouri, northern Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, SC, NC, that whole belt right through there we see a lot more diversity of crayfish species. The clay-dwellers are usually like a reddish or a black/red shad color or a brown/orange pumpkin because they are clay-dwelling and burrowing species, but up north, those color crayfish are less likely to be common. Green pumpkin or dark browns are more common crayfish color up north. Up north the gold shiners and alewives are present. Down south, gizzard shad. That’s how the forage changes just going north and south.

It’s more than just temperature that triggers the crayfish move, but a combination of the tilt of the earth toward the sun and the length of day, as the days get shorter. The most obvious indicator or gauge we have of the days’ shortening is water temperature because as the day gets shorter, there is less UV and less sun hitting the lake heating the water, so it doesn’t stay heated up as long as in summer. It doesn’t have that retained higher temperature. So the dropping of water temperature is a reflection of the shortening of the day. Factor that with a lake that may have draw down, these are all indicators to crayfish that the time of winter is coming closer and that’s when they’ll be triggered to move. Again, it could be closer to 60 degrees up north when the crayfish start to trigger to move, around 65 degrees through the middle of the country, and say 70 at the southern end.

Across the entire country, we’re mostly talking of a falling water temperature from 70 to 60, give or take a few degrees, that triggers the crayfish move.

| The Lake Location Connection |

A lot of your lakes that have drawdown, they do not have a whole lot of aquatic vegetation rimming the shoreline just because of the fluctuating water level. Any grass that gets seeded each summer, gets dried up during the ensuing drawdown. What happens is the harder bottom areas, especially in drawdown lakes, weedy stuff that was able to provide habitat during the summer, the aquatic plants that got rooted to rocks or to hard bottom becomes the preferred crayfish habitat for a few months – until late fall (coinciding with drawdown) which gets the crayfish population migrating into nearby burrowing areas of softer bottom.

A lot of your lakes that have drawdown, they do not have a whole lot of aquatic vegetation rimming the shoreline just because of the fluctuating water level. Any grass that gets seeded each summer, gets dried up during the ensuing drawdown. What happens is the harder bottom areas, especially in drawdown lakes, weedy stuff that was able to provide habitat during the summer, the aquatic plants that got rooted to rocks or to hard bottom becomes the preferred crayfish habitat for a few months – until late fall (coinciding with drawdown) which gets the crayfish population migrating into nearby burrowing areas of softer bottom.

So our main locus for finding fishing hot spots is to focus on bottom substrate composition in lieu of vegetation on drawdown lakes.

The thing about drawdown too, what makes it so good is as the shoreline recedes, you can more clearly see the substrate which would normally be underwater or hidden by shoreline vegetation.

What we are looking for are the transition zones from hard to soft substrate and especially the areas where hard and soft substrate mix or overlap.

The transition zones in a lot of cases are along the sides of points. Points are typically extensions of shallowing portions of channel swings or some sort of shoreline edge connection to the main lake. There’s often some sort of transitional substrate zone going down the sides of points – those are usually areas that have the rock to clay transition. The harder, outer tips of the points gradually transition down the sides, and give way to the softer, sediment-filled back pockets. Some points do, some points don’t.

The typical rule of thumb is that the slope of the bank above the water is typically the slope of the bank below the water. So if you see a flatter bank transitioning to a steeper bank, those areas are always good to look at. Those sharp slopes could signal underwater channel bends or swings, but a lot of guys miss them since much of the transition zone is underwater and can’t be seen except on electronics. Where you want to be is in the transition zone, that ten to fifteen yards into each stretch of hard and soft and including the mixture in between. That’s going to be where a lot of fish are setting up in that area. The fish can detect the craws there, and those bottom transition areas are what the fish are going to be interested in. If you are good at reading your graph, you’ll see a double echo or a thinner bottom line (a harder ping) over the hard bottom, and a thicker bottom line (or softer ping) on softer bottoms. If at all possible, you can use any clues from what appears on the shoreline as a visual guide to get you into the transition zone, along with your electronics.

The most obvious places with sharp slope changes are of course, emergent points. This time of year I like the shorter points, the ones that are not as long and tapered. The steeper-looking points can be best and in some cases, even rounded points. Those are usually the areas that the fish are going to winter up on. They’ll get onto the long, gradually-tapered points, but it seems more in the spring and summer months. Right now, during the drawdown and crayfish move, focus on finding the substrate transition zones down the sides of the points, and focus more on your shorter points. This time of year, the bass are naturally attracted to such areas because that’s where the crayfish move is happening.

| The ima Skimmer Topwater Connection |

You’ll know you are in the right areas around this time of year, you may find bass with their noses scuffed up from rooting in the rocks for craws. Also when fish are feeding heavily on crayfish, you can feel their stomachs and the hard edges of the crushed-up crayfish can feel like gravel in their stomachs. Those are good areas where you want to be.

You’ll know you are in the right areas around this time of year, you may find bass with their noses scuffed up from rooting in the rocks for craws. Also when fish are feeding heavily on crayfish, you can feel their stomachs and the hard edges of the crushed-up crayfish can feel like gravel in their stomachs. Those are good areas where you want to be.

A lot of guys are going to try to match the hatch with crayfish jigs or soft craw baits and so on.

Matching the hatch is great to do especially in a tournament or on a day when the fishing is slow or the fishing is tough, then matching the hatch is good to do. When things slow down on tougher days, you may need to fish slow-moving bottom contact baits.

But this time of year, most days you don’t have to do that because fish are typically concentrated, the competition is high, and they are very, very aggressive.

So despite the prevalence of crayfish which serves to aggregate bass in these areas, the real thing you’ve got to remember is a lot of fishing is just:

- covering water,

- keeping the bait in the strike zones to which fish will commit (surface, mid-depth and/or bottom) and

- throwing baits that don’t necessarily match any hatch but are nevertheless effective both in their action and have the right sound for a given area.

And that’s where the ima Skimmer (surface strike zone) and the ima Flit jerkbait (mid-depth strike zone) I think are very, very successful.

Keep in mind too that there are many baitfish running down the sides of points into the small run-off areas and sedimented, sun-warmed pockets that often exist at the shallow ends.

Use a run and gun technique. Look for those specific areas and look for the sides of the points where deep water butts up right next to it. Tune in to those transitions and just go after it. You could hit eight or nine of these areas with nothing and in the next one, load the boat.

You can cover water much more quickly this time of year by using things like the ima Skimmer topwater stickbait especially when that surface water is still warmer than 65 degrees. If it’s a little windier, the ima Roumba grabs more of the surface and throws a more visible wake on windier days. But most days, the Skimmer’s what I use this time of year when the water remains warm enough for bass to commit to a surface strike.

A lot of people put the Skimmer in the category of other walking baits. I think the Skimmer is much different. It’s kind of in its own category. It looks like other walking baits, but it doesn’t push water, it cuts through the water. To see the design of this bait, the body cross-section is a teardrop shape. And in fact the water will flow over its back and will create a swirl right behind it every time you jerk it, which a lot of baits won’t do that. Other walking baits will push water and splash but the Skimmer is one that actually creates a swirl behind it. If you look at the Skimmer on videos or when you are first working it, you’ll mistakenly think that fish are swirling at it – and that’s what it does, it creates the idea, the impression that there’s a fish trying to eat it. So a fish is more likely to become competitive when it thinks another fish is there (but really is not there). So it will see the surface swirl – and try to get the Skimmer before another fish gets it. That’s the beauty of this bait – that boil, that swirl behind the Skimmer.

If you’d like to see the Skimmer in action, there are ten short video clips that show the Skimmer’s action at

Also, people have got to remember that the preferred temperature range of the largemouth bass metabolism is roughly 72 degrees. With a 72 degree surface temperature, 20 feet down might be 60 degrees. So fish are obviously going to be active on the surface and chase for bait when the surface layer of water isn’t far from 72 degrees. And that’s when topwaters like the ima Skimmer are really effective – when the surface water temperature is anywhere above 65 degrees or so.

| The Baitfish Connection |

The late fall season is Mother Nature’s way of giving one last opportunity for bass to get a lot of fat in them, necessary to produce their eggs over winter. The high protein of the crayfish is only one part of the banquet. The other part is the high protein of the prevalent baitfish that are migrating down the sides of these very same points making their way to the backs. The deal is a concentration of everything on the sides of these short points or transition zones from deep hard bottom to shallow soft bottom. You’re having areas that are just packed full of options for the bass. There are baitfish moving, crayfish moving. It’s just a cornucopia of plenty for bass before going into winter hibernation. Just before their metabolism decreases, they are putting on weight for next year’s spawn. They’re having one last good feed right now before winter and then they’ve got one good feed as things warm up in the spring to recharge strength before the spawn.

The late fall season is Mother Nature’s way of giving one last opportunity for bass to get a lot of fat in them, necessary to produce their eggs over winter. The high protein of the crayfish is only one part of the banquet. The other part is the high protein of the prevalent baitfish that are migrating down the sides of these very same points making their way to the backs. The deal is a concentration of everything on the sides of these short points or transition zones from deep hard bottom to shallow soft bottom. You’re having areas that are just packed full of options for the bass. There are baitfish moving, crayfish moving. It’s just a cornucopia of plenty for bass before going into winter hibernation. Just before their metabolism decreases, they are putting on weight for next year’s spawn. They’re having one last good feed right now before winter and then they’ve got one good feed as things warm up in the spring to recharge strength before the spawn.

When we get closer to 60 degrees in most areas, except way north where it’s probably more like the 60 to 55 range, once you get close to that temperature, that’s an indicator in my book that the crayfish for the most part, a lot of the crayfish are done burrowing.

As you get closer to the 60 degree range in the middle and south of the country, from Missouri east to North Carolina, south to South Carolina, back across to Texas and about everything in between, a lot of those crayfish will be burrowed as you get closer to 60. So the bass will tend to shift more toward the baitfish bite, and those baitfish will tend to suspend in the deeper water, especially as the water gets colder, and this is all relative to water color of course.

As the surface temperature. tapers down to 60, now those fish are forced to not go to where their preferred temperature is or where they feel most comfortable but where the food is. The crayfish are burrowed or no longer a forage option at this water temperature. So the forage base at this point shifts to suspended baitfish in relatively deeper water.

| The ima Flit Jerkbait Connection |

If they’re no longer eating the Skimmer topwater, as the water gets closer to 60, they’re going to start turning on the deeper-running Ima Flit jerkbait.

With a 60 degree surface temperature, it could be 50 to 55 degrees around 15-20 feet deep so the bass at that point are already getting into the lethargic winter stage. They’ve got to slow down, are less likely to commit to the surface because not only are they more lethargic, but they are also sitting in deeper water. So you’ve got to get down more to them. You’ve got to get down to that 6-8 foot range and meet them halfway with something that’s closer to the strike zone – and that’s where the Flit comes into play.

| The Rod, Reel and Retrieve Connection |

A guy could get away with the same type rod for both the ima Skimmer topwater surface walking bait and the ima Flit jerkbait. And the way to work both is with the same walking motion. Keep the rod tip below waist high and just work the rod with the short twitching downward motion to where you can get both the Skimmer and Flit to have side-to-side darting actions on every downward rod stroke – known as ‘walking the dog.’ The only difference is, of course, the Skimmer dances on the surface whereas the Flit dives 6-8 feet, and as the water gets colder, add more pauses to your retrieve with the Flit jerkbait.

A guy could get away with the same type rod for both the ima Skimmer topwater surface walking bait and the ima Flit jerkbait. And the way to work both is with the same walking motion. Keep the rod tip below waist high and just work the rod with the short twitching downward motion to where you can get both the Skimmer and Flit to have side-to-side darting actions on every downward rod stroke – known as ‘walking the dog.’ The only difference is, of course, the Skimmer dances on the surface whereas the Flit dives 6-8 feet, and as the water gets colder, add more pauses to your retrieve with the Flit jerkbait.

My rule of thumb for selecting a topwater/jerkbait rod for a bass boater is that I typically recommend a rod that can point straight down when you’re up on the bow of the boat, to where the rod tip does not slash the water on the downstroke. Now, the ideal rod length is relative to your height. One must remember I am 6’5″ so what is comfortable for me may not be comfortable for a guy who’s 6′ tall or 5′ 6″.

The Fenwick Elite Series Pitchin’ Stick I most often use only comes in one length, 6’9″. The model number is ECPS69MH-F. I like this rod for jerkbaits and topwaters. Another one I also like is the Fenwick Techna AV 7’0″ MH, Model AVC70MHF. It is extremely light and sensitive with a good tip action.

As I say, I like where the rod tip is still out of the water on the downstroke. So for a guy who’s 5’6″ or shorter, you may want a 6′ rod. Anglers approximately 6 feet tall may want a 6-1/2″ foot long rod. You want it just short enough to where you are not slashing your rod tip into the water every time you work the bait. As I say, you work both the Skimmer and Flit nearly the same – with a walking motion. Whether it be on the surface or 6-8 feet down, it is the same rod motion, the same twitch motion and what I’m comfortable with using is a 6.3:1 gear ratio reel, which is the most common gear ratio for baitcasters. The only difference is I use 12 lb mono for the Skimmer topwater which floats. When you go to fluorocarbon, it will sink and it will disrupt the action of the Skimmer. With the Flit jerkbait, yes, you can get away with 12 lb mono too – but I am a bigger fan of 10 lb test fluorocarbon which sinks. So when I go to a jerkbait, I lean more toward fluorocarbon just because of the sinking factor that helps me to obtain that deeper range, thereby getting down there a little closer to the fish.

So I prefer the same rod action for both the Skimmer and Flit, rod length matched to your height, and a 6.3:1 gear ratio. I’m using an Abu-Garcia Revo personally, and in my case I use the Fenwick Elite and Techna AV series rod. But most important point for you here is you’ll be much better off to just match the rod length you use to your height. The objective being that the tip won’t hit the water surface on the downstroke.

For the guys who are fishing off the bank (and there are many, many more of them than fish off of boats), whenever you are fishing from the bank always go for the longer rod. That’s why we see surf fishing rods along the coast that are 8-9 feet long. That’s why fly rods are typically 7-8 feet. The same thing applies to bass fishing from the bank. Use the longest rod you can get away with. For bass fishing, that mostly means a 7 footer. If you can use a 7′ rod without casting into trees, I say go for it, regardless of your height. If there’s a lot of overhanging shoreline cover, you may have to go to a shorted rod – but go with the longest rod you can get away with, in order to make longer casts. On the bank, there’s a lot of noise – footsteps on the bank, snapping a stick you step on, that can be picked up by fish and is associated with predation – bass are more wary of noises coming down the bank because that’s where many predators come down to the waterline. So bass are more naturally wary of noises coming from the bank rather than noise coming from a boat. Working a Skimmer or Flit from shore, keep you rod tip down near the water level, kind of down on an angle instead of straight down.

Well, we’ve made a lot of different connections today to try to make the puzzle of late fall fishing patterns seem clearer. Thank you for reading along. I hope you get out there this weekend and connect on your own with the ima Skimmer and Ima Flit.

– Michael

| Thank You! For Reading the ima EMAILER |

ima’s a big name in Japan where ima is known for its hardbaits. ima is now making a big name for itself in North American too, with the help of U.S. bass pros who have designed new ima hardbaits for the USA. Find these great ima Baits at BassTackleDepot.com